Undergrads Take to the Wind Tunnel to Build a Better Surfboard

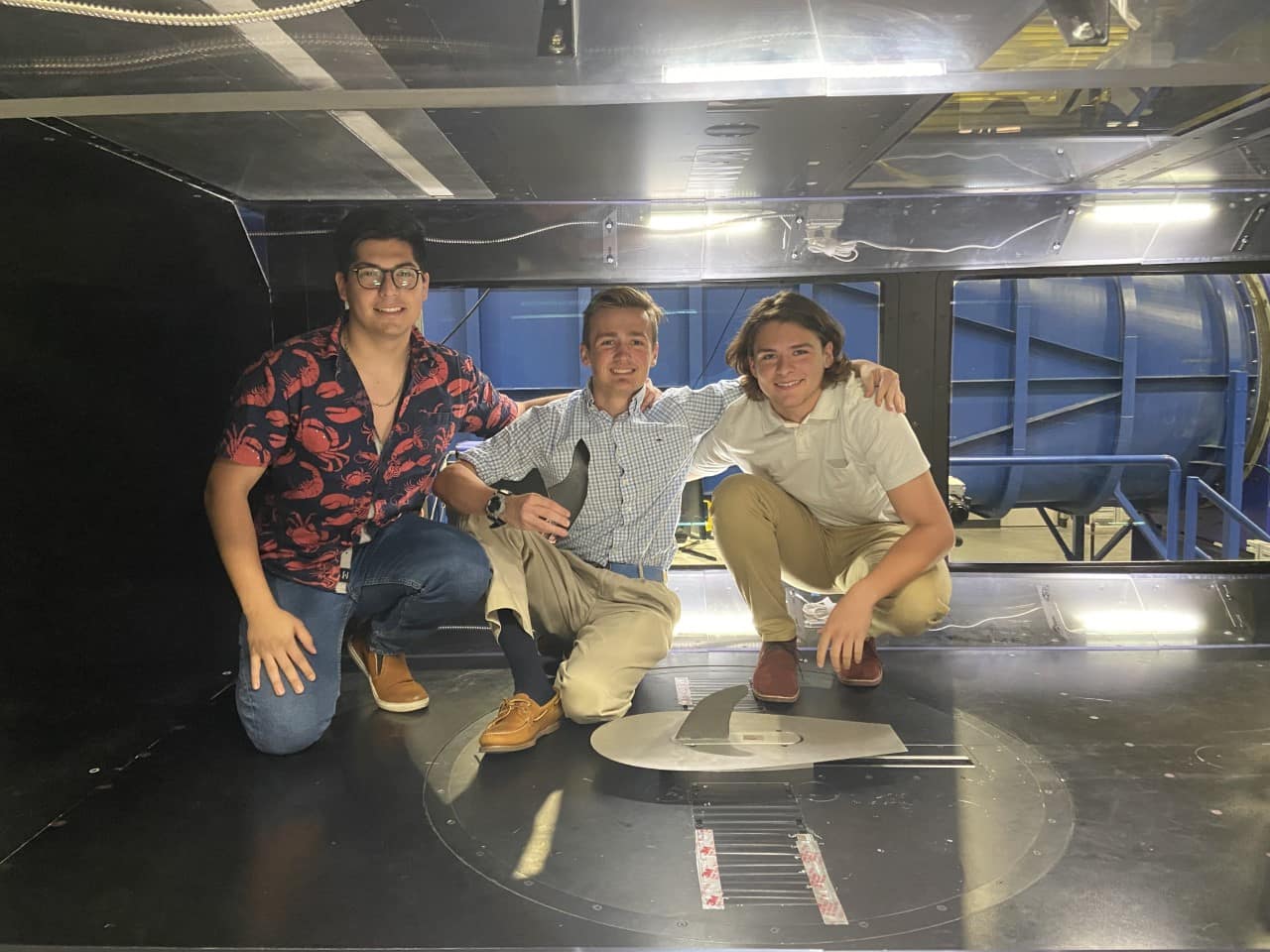

For the very first time since its installation on campus in 2018, the new subsonic wind tunnel on Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Daytona Beach Campus was made available to undergraduate researchers last semester — and a group of Aerospace Engineering students intended to take full advantage of the opportunity.

Their mission: Design and test the perfect surfboard fin.

This, however, was not always the goal. Initially, the group — representing Embry-Riddle Surf Club and Project SHRED (Surfing Hydrodynamic Research with Engineering Design), founded by student Noah Ingwensen for a final project in his Experimental Aerodynamics course— went to a smaller, lower-speed wind tunnel on campus to examine the efficiency of common surfboard fins. The data was inconclusive, though, which led to the formation of a testing team for follow-up research, led by senior Patricio Garzon, junior Andrew Ankeny and sophomore David Paolicelli. Funded by Ignite Grants through the Office of Undergraduate Research, the team went to the new 16,000-square-foot Wind Tunnel Annex housed in the John Mica Engineering & Aerospace Innovation Complex (MicaPlex), for further testing. The tunnel’s capability of delivering wind flow speeds up to 230 mph proved to be a difference-maker, offering insights the team did not anticipate.

“We knew how similar the physics behind surfing was to flying, but once we realized how little research and technical design some surfboard companies put into their products, we decided to take up a challenge to produce a fin that performed better when compared to similar ones on the market,” Paolicelli said.

Further, the students incorporated a winglet into traditional surfboard fin design, borrowing the feature from modern aircraft design.

“People have been dedicating their lives to improving the surfboard since surfing broke into mainstream culture,” Ankeny added. “However, the effects of the fins have been mostly ignored.”

These students are going to be much more prepared to solve new and challenging problems when they enter the workforce than they might otherwise be.

For Wind Tunnel Director and Distinguished Professor of Aerospace Engineering J. Gordon Leishman, the students’ hypothesis makes perfect sense.

“Testing the fin in air at higher flow speeds can mimic the hydrodynamic effects of water,” Leishman said.

“In a physical sense, air and water are no different, both being classified as fluids,” Garzon added. “For this reason, the study of the fluid dynamics behind them is essentially the same. We are able to take the data we collect from putting our fins in a wind tunnel and say with confidence that the forces felt in water will be the same if we match the Reynolds number, a non-dimensional similarity parameter that describes the relative viscous effects felt in the fluid.”

The same logic applies to aircraft design.

“By scaling down the size of their machines, airplane manufacturers can build and test a model of a new design that will give them an indication of how a full-size aircraft would hold up in essentially any condition,” Garzon said.

Wind tunnel testing offers students a glimpse into a world that extends far beyond basic classroom aerodynamic theories.

“Aerodynamics is just one subset of a broader field called fluid dynamics,” Leishman said. “Engineers encounter a broad and diverse range of problems in fluid dynamics, and often these problems are for other than traditional aircraft.”

Additionally, aerodynamics plays a key role in sports: football, baseball, swimming, car racing, etc. Serving as a point of entry for students, interest in these areas can lead to thinking about the role of fluid dynamics to improve in the sport — and better understanding often comes from experimentation.

“These types of problems motivate students to go beyond what they learn in the classroom and learn how to innovate and solve problems using the resources that are available to them, as well as engaging professors with the expertise and experience that can help them,” Leishman said. “These students are going to be much more prepared to solve new and challenging problems when they enter the workforce than they might otherwise be.”

Access to cutting-edge facilities like the new wind tunnel — as well as the Computational Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the Resin 3D-Printer at the MicaPlex’s Material Research Laboratory — give them that chance.

“Working with Project SHRED has given me a unique opportunity to develop skills in experimental design,” Ankeny said. “Our advisors have given us such great opportunities and feedback on all our work, and they have worked tirelessly with us to hone our methodology to produce the best results.”

“Working on surfboard fin design has given us the chance to gain more wind tunnel testing exposure than most,” Garzon added. “In addition to working with state-of-the-art equipment at the Micaplex, Project SHRED has given us the opportunity to apply the theory we learn in the classroom to real-life problems. Not only are we gathering data and doing the calculations, but we are also analyzing that data and interpreting what the numbers mean.”

It is that sort of hands-on experience, they say, that will help kick-start their careers after graduation.

Mike Cavaliere

Mike Cavaliere