Fiction May Offer Clues to Fake News Impacts

In Philip K. Dick’s 1969 science fiction novel Ubik, the Hollis Corporation sets an explosive trap for members of rival Runciter Associates after Runciter tries to convince the public that their privacy is threatened by psychic Hollis employees.

“Runciter’s propaganda campaign is a perfect example of brainwashing,” said rising sophomore Ethan Hale, an engineering physics student in the Honors Program on Embry-Riddle’s Daytona Beach, Fla., Campus. “In the book, Runciter’s ads are all over the place – on matchboxes and TVs every hour. People start to fear Hollis, and in turn, people gaslight each other through peer pressure so that everyone thinks the same way.”

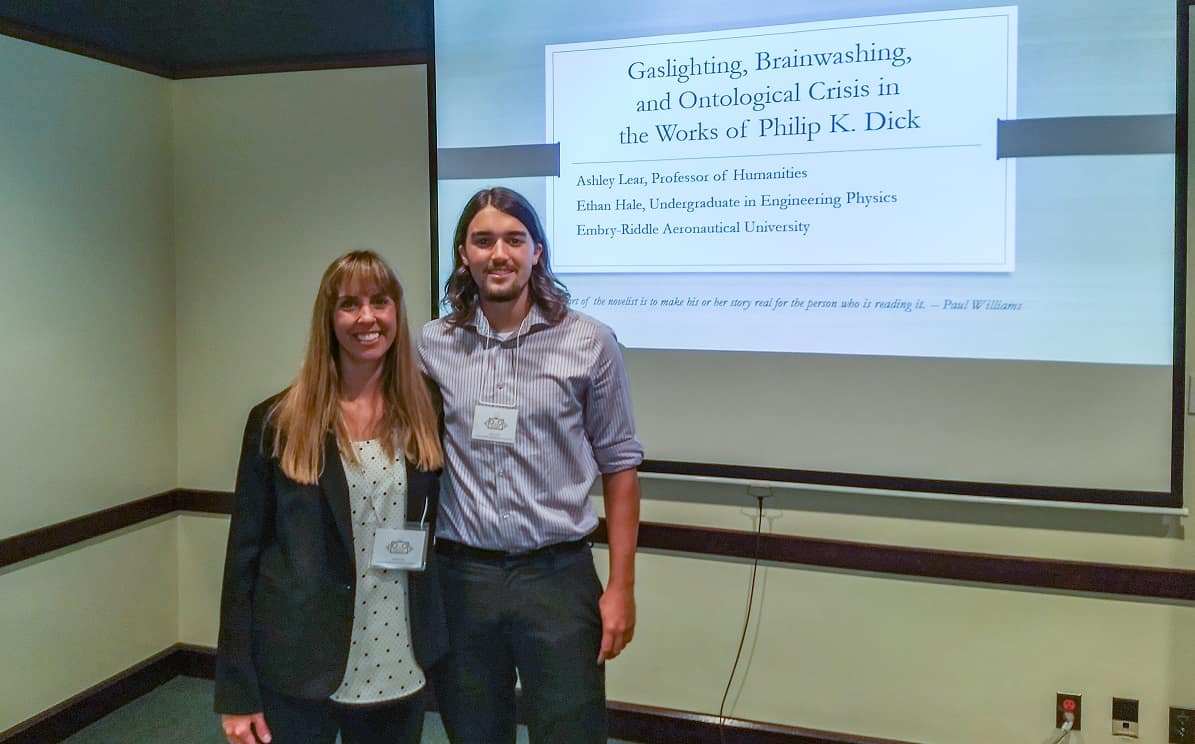

As part of research directed by Professor of Humanities Dr. Ashley Lear, Hale looked at how Dick’s fictional scenarios might inform real-world reality shifts caused by propaganda campaigns and fake news distributed via social media.

The topic is timely: During the most recent U.S. Presidential campaigns, the political data firm Cambridge Analytica gained access to private information about more than 50 million Facebook users. Further, MIT scholars recently reported in the journal Science that lies spread much faster than the truth, and humans, not computer “bots,” are responsible for redistributing most misinformation.

“As we all become more aware of these issues,” Hale said, “my hope is that eventually people of all ages will start to be a little more discerning about what they’re seeing and reading, and how it affects their sense of reality.”

A native of Columbia, Mo., Hale was taking Lear’s Archaeologies of the Future class when he realized her literary research might help him feel more engaged with campus life. “I was at a point where I was not in any clubs or student organizations,” Hale explained. “I really wanted to join something, but hadn’t found a good fit. I asked Dr. Lear after class if I could work with her and she said, `Absolutely.’ She’s incredible.”

His research with Lear, entitled “Gaslighting, Brainwashing and Ontological Crisis in the Works of Philip K. Dick,” was presented at the Science Fiction Research Association Conference on July 3. Now, Hale will work with his mentor to develop a related journal article.

While Embry-Riddle is primarily known as a leading aviation and aerospace university, Humanities and Composition courses allow students to round out their world view and fine-tune their emotional intelligence, Lear said. “Humanities-focused education provides students with empathy and compassion, and the ability to forge relationships in their different career pursuits, which is essential to leadership in any setting,” she added.

Three Reality-Shifting Techniques

Science fiction offers a thought-provoking way to study how a person’s reality can be challenged and even changed against their will, Lear noted.

Gaslighting was so-named after the 1944 movie Gaslight, in which an evil man makes the woman who loves him think she’s crazy. “He moved in with her and started walking around the attic to find her family jewels,” Hale said. “Whenever he was up there, the gaslights would flicker. She would ask him about it, but he would just say, ‘You’re crazy.’”

By comparison, brainwashing involves force-feeding a false reality to people by repeating the same propaganda until they believe it.

The Matrix, a 1999 science fiction movie, offers a perfect example of an ontological crisis. Computer programmer Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) “learns that his entire life is a computer program called The Matrix and he’s being harvested for body heat energy by machines that have taken over the world,” Hale said.

Hale’s trip to the Science Fiction Research Association Conference at Marquette University in Milwaukee was supported by the Office of Undergraduate Research, through a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship, said Kadie Mullins, director of undergraduate research. Lear noted that it was a national conference primarily for faculty and a few graduate students.

Hale was the only undergraduate presenter at the conference.

He was grateful for the support. “I really appreciated how Embry-Riddle gave me the opportunity, as an engineering physics student, to do something with the humanities that wasn’t necessarily related to my major but allowed me to go outside the box and get some good stuff for my resume,” Hale said. “I wouldn’t have done the project or gone to the conference without Dr. Lear’s encouragement. I feel like that type of knowledge helps me be a more well-rounded student. It was also a great break over the summer from my engineering studies.”

In addition to an undergraduate degree in engineering physics, Hale hopes to pursue an Embry-Riddle M.B.A. degree. He said he feels more engaged with campus life now.

Don’t look for him on Facebook, though. “I have no social media,” he said. “I prefer face-to-face conversations.”

Ginger Pinholster

Ginger Pinholster