Hero Pilot Inspires Embry-Riddle with Lessons Learned from Lifesaving Flight

As one of the first female fighter pilots in the U.S. Navy, Tammie Jo Shults was initially turned away by the Air Force and Army, even told by recruiters and high school counselors that aviation was no place “for girls.” Later in her career, while flying as a Southwest Airlines captain, an engine exploded mid-flight, resulting in an emergency in which she and her first officer, Darren Ellisor, heroically landed the aircraft safely, saving the lives of 148 passengers and crew onboard. Tragically, one life was lost.

“Never let offense get in the way of a great opportunity,” she told a crowd of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University students and staff, during the Center for Aviation and Aerospace Safety’s inaugural Speaker Series event last week. “I hadn’t been told answers. I’d been told opinions.”

Those opinions didn’t stop her from chasing her dreams, however — neither did what was, at the time, an unwelcoming industry culture.

“Every squadron I checked into, I was the lone female,” Shults said, adding that she was sometimes met with suspicion when she arrived at bases. “The shockwave was transparent, and the attitudes extreme.”

In her book, “Nerves of Steel: How I Followed My Dreams, Earned My Wings, and Faced My Greatest Challenge,” Shults outlines the combination of training and instincts that led to her and Ellisor successfully dealing with a disintegrating engine that punctured a hole in the side of the aircraft, resulting in a rapid depressurization. Because of damage to the engine and part of the airframe, they struggled to control the airplane during descent, approach and landing. Quick to deflect praise, she emphasized the successful landing was due to the efforts of the entire crew, including the flight attendants, who were dealing with chaos in the cabin.

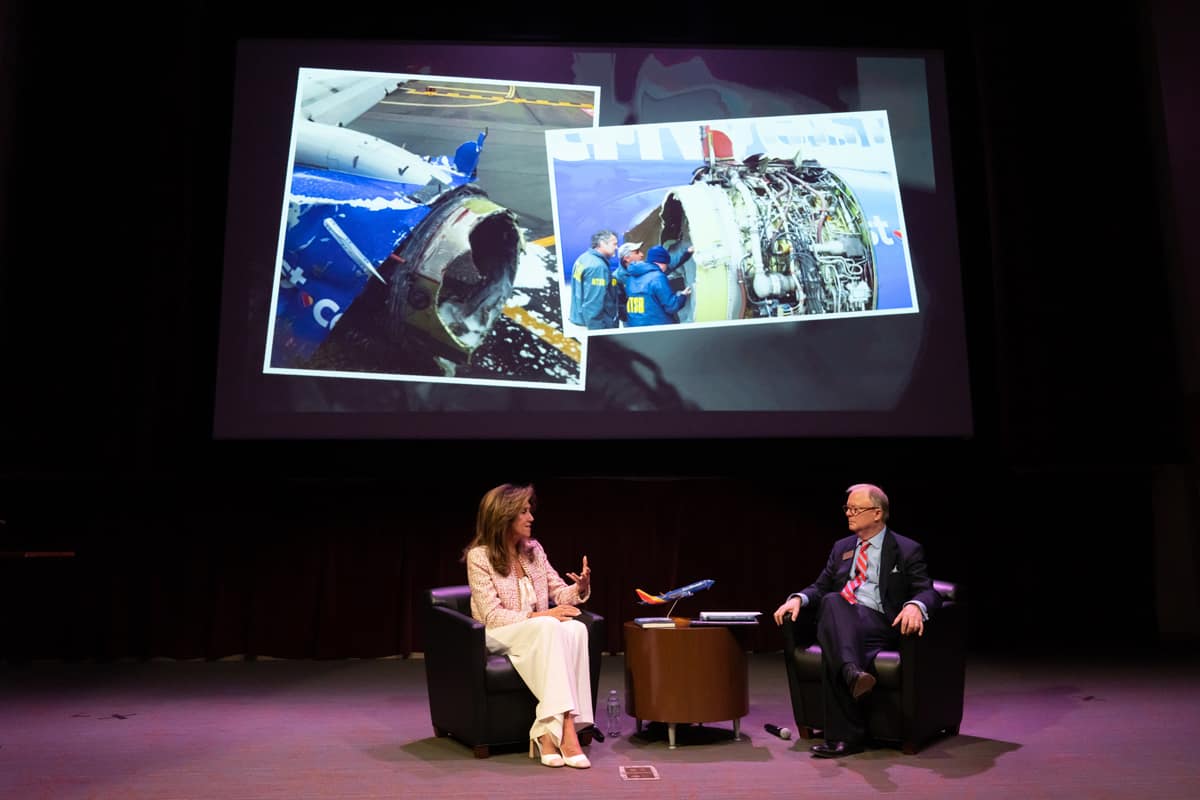

Capt. Tammie Jo Shults was interviewed by Center for Aviation and Aerospace Safety head Robert L. Sumwalt, former chair of the NTSB, which led the investigation of Shults’ mid-flight emergency. (Photo: Embry-Riddle/Bernard Wilchusky)

“Habits on a good day become instincts on a bad day,” Embry-Riddle President P. Barry Butler, Ph.D., read from Shults’ memoir before welcoming her onstage. “It is exactly that type of unwavering dedication that has enabled her to reach success, and it is exactly those types of habits that we at Embry-Riddle strive to instill in our students.”

The talk was moderated by the Honorable Robert L. Sumwalt III, former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which served as the investigating agency of Shults’ emergency flight. Sumwalt currently serves as the executive director of Embry-Riddle’s Center for Aviation and Aerospace Safety, which aims to improve the safety for all who fly, through research, education programs, consulting services and thought leadership events like this one.

“We’d been cleared to 38,000 feet and, at 32,600 feet, we heard an explosion and just fell like we’d been T-boned by a Mack truck,” Shults said, remembering what she calls “that kaleidoscope of a day.” “It was a chaotic motion … all at once.”

She and Ellisor could hardly read the flight instruments because of how badly the aircraft was shuddering. Smoke was in the cockpit. Condensation was dripping from every surface due to depressurization.

She remembers the roar of the aircraft, and how she couldn’t hear the sound of her own voice in her headphones.

“It’s a little isolating when you can’t breathe, hear, speak,” she said. “If you haven’t had something dramatic happen, adrenaline — there’s no alchemy in it. It won’t give you an epiphany … but it does make you recall what you do have stored pretty quick. … Adrenaline, I think, gives you speed of thought … a sense of priority.”

For your priorities to be rational and clear, however, you need to amass a wealth of time in the flight deck.

“How you get judgement is through experience — and you had that experience,” Sumwalt told Shults.

Amid the blur of the emergency, Shults remembered facts from past crashes that she had read about. They reminded her what not to do while she mentally “cycled through options.”

“All those procedures and checklists are foundational,” she said of the industry standards learned in flight training, but maintaining situational awareness, she believes, is what kept her and, by extension, 147 other people on that plane alive. “Aviate, navigate, appropriate.”

That’s the key to remaining calm.

“It’s not magic. It’s not something you’re born with or you’re not,” Shults explained. “It’s just taking the time to learn your systems and your procedures and your checklists – but you being the master of them. … We feel the most stressed when we don’t know what to do.”

Mike Cavaliere

Mike Cavaliere