Embry-Riddle, UCF Partner to Map Oyster Reefs Using UAS

Twenty-one oyster reefs near Edgewater, Fla., are the focus of a new partnership between Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and the University of Central Florida (UCF) to develop methodologies for remotely mapping regions that would otherwise be difficult, and expensive, to monitor on site.

The goal of the research is simple: Using Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), survey the reefs to gather information, including exact oyster counts and virtual imaging, without ever visiting the locations in person. If the project proves successful, according to Dr. Dan Macchiarella, professor of Aeronautical Science, it would signal a clear change in the way environmental data have traditionally been collected. It would mean progress.

“The alternative to remotely sensing is to physically travel to a location, and in the case of oyster beds, many are located in hard-to-access areas, like the middle of mangrove tree stands,” Macchiarella said. “There are other applications for remote sensing to sample wildlife, too, including using the technology to locate fish nests in remote river locations.”

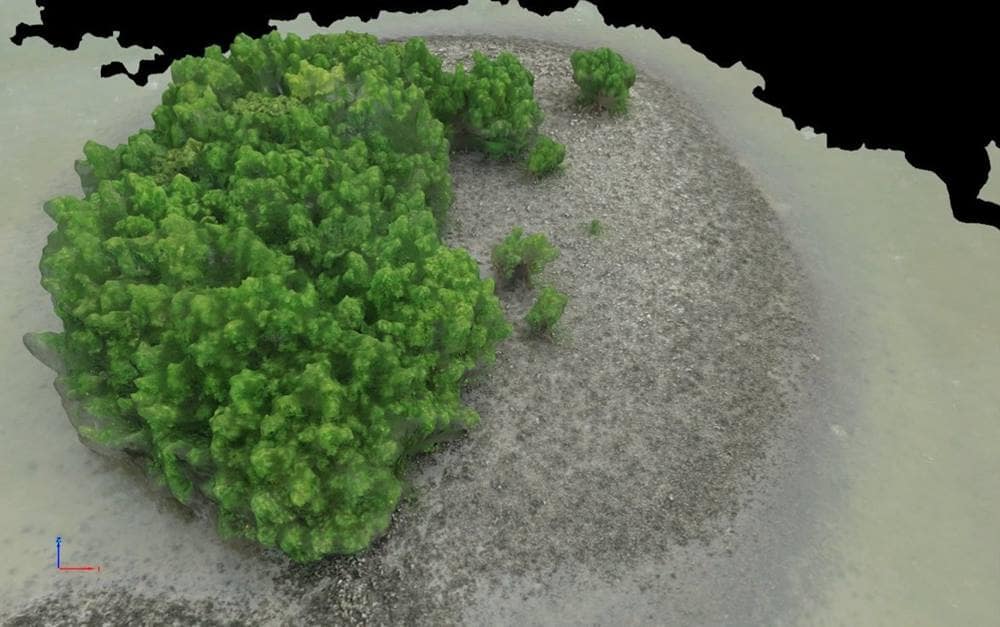

UAS cameras captured visuals that were processed into virtual renderings of oyster reefs near Edgewater, Fla. (Photo: Embry-Riddle)

The project, conducted by Macchiarella, Unmanned Aircraft Systems Science students Liam Griffin, George Gebert and Kyle Zier, and Drs. Linda Walters and Giovanna McClenachan, of UCF’s Department of Biology, stands as Embry-Riddle’s first partnership with UCF’s National Center for Integrated Coastal Research. Although centering on coastal mapping, the same technology can have a variety of other applications, as well. In Tanzania, for instance, drones are used to monitor elephant herds as part of an anti-poaching program. With UAS images currently being 60 times more detailed than even the best visual data captured by Google Earth, possibilities will continue to expand in the United States as the Federal Aviation Administration moves toward effective integration of UAS into the National Airspace System.

“In the future, more and more environmental-monitoring tasks will be accomplished using UAS, due to the inherent mobility, aerial perspective and cost efficiencies of these systems,” Macchiarella said.

And that means more and more learning opportunities.

In-the-field work is essential to a good degree program, especially when you have to work as a team toward a common goal.

For Griffin, who assisted with setting up the aircraft for takeoff and served as the project’s visual observer, the most challenging aspect of the research was finding a safe place for the UAS to launch and be recovered. Forced to manage tide changes to ensure stability of the launch and landing locations, the team was reminded that the unique circumstances of each test site must be taken into consideration in order for any mission to be successful.

“Within this industry, there is a lot of forward moment and upward growth,” said Griffin, a fourth-year student who also serves as the UAS Technology Club’s events coordinator at the Daytona Beach Campus. “So, I like to take every opportunity that arises. I think that any in-the-field work is essential to a good degree program, especially when you have to work as a team toward a common goal.”

The focus of Dr. McClenachan’s research is landscape-scale historical changes and disturbance-response in the Indian River Lagoon system around Cape Canaveral, Fla. With the help of Embry-Riddle’s College of Aviation, she is working to uncover the driving forces behind oyster reef and mangrove island ecosystem conversion across periods of marsh development and modification.

Mike Cavaliere

Mike Cavaliere