Powered by Propellers, Seagliders Could Cruise New Terrains

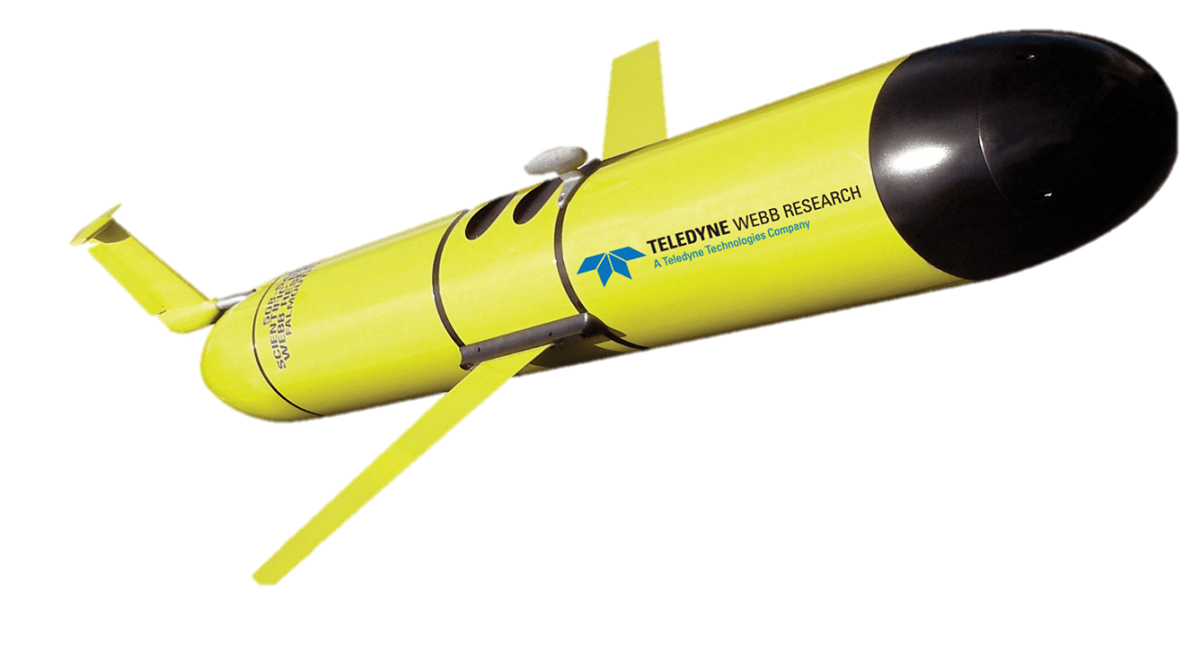

Under the seas, bullet-shaped vehicles with wings glide slowly up and down in a see-saw pattern, reaching depths of 1500 meters before rising again. Known as seagliders, these autonomous underwater vehicles conduct environmental and security monitoring for many months at a time, stopped only by barnacle growth or shark attacks.

Unfortunately, seagliders can’t easily navigate through shallow basins or currents because they’re propelled in a passive fashion, by releasing water to rise and taking on water to sink. The resulting yo-yo movement allows seagliders to cover a mere foot per second for every two pounds of thrust, which limits them to relatively calm offshore waters.

Embry-Riddle researcher Christopher Hockley wondered whether more powerful, agile seagliders, equipped with conventional propulsion systems, could somehow operate as efficiently as those propelled only by changes in buoyancy. That would make it feasible for seagliders to patrol fast-moving, shallow waters. His conclusion – presented at the Xponential 2018 of the Association for Unmanned Vehicles Systems International (AUVSI) – challenges conventional assumptions, said Brian Butka, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

If a propeller-based propulsion system has an efficiency rate of 43 percent or higher, it can outperform buoyancy-driven propulsion for use in seagliders, said Hockley, a new visiting faculty member at Embry-Riddle who just received his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering on the Daytona Beach Campus.

“Seagliders under conventional propulsion can absolutely be more efficient and go farther and faster than seagliders using buoyancy propulsion,” said Hockley, who also earned his undergraduate degree in aerospace engineering and his Master’s in mechanical engineering at Embry-Riddle. “Instead of one foot per second, these seagliders would do three to four feet per second, at least.”

Although it seems counterintuitive, Hockley said the trick is that buoyancy systems power up at the surface and then power down after sinking. All that starting and stopping is inefficient. “With a propeller-based system, you’re continuously using a little bit of energy,” he noted, “so the propeller just needs to be 43 percent efficient to compete with a buoyancy system.”

This revelation means seagliders could navigate terrains such as California’s San Diego Basin and the Chesapeake Bay in the Mid-Atlantic region – areas where additional environmental research and security monitoring could prove helpful. Seagliders offer unique capabilities in such settings. Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, for example, an iRobot seaglider capable of sinking to depths of nearly 1000 meters was dispatched to study billowing underwater plumes of oil, the Boston Globe reported.

With propeller-driven seagliders optimized for efficiency, “You could go faster and you could go against the current,” Butka said. “Most importantly, propellers are cheap and reliable compared with buoyancy engines, which tend to be fussy and expensive.”

Hockley’s research, which was also presented at Xponential 2017 and the 2016 Aquatic Solutions Conference, involved “lots of math,” he said, laughing – “lots and lots of math.”

Previously an Embry-Riddle teaching assistant, Hockley has taught classes for the Engineering Sciences, Aerospace Engineering and Mechanical Engineering departments. He has also served as a team lead for the university’s Maritime RobotX Team.

“I’m delighted that Chris has joined Embry-Riddle as a visiting faculty member,” Butka said. “He brings a wealth of practical experience in autonomous vehicles in both the aerospace and nautical domains. His commitment to excellence in teaching will serve our students very well.”

Ginger Pinholster

Ginger Pinholster