Embry-Riddle Hurricane Researcher Hits Plane-Threatening Turbulence

As Hurricane Melissa threatened to unleash devastation in the Caribbean, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University meteorology professor and researcher Dr. Josh Wadler was experiencing the sheer might of the Category 5 hurricane, flying directly into its eye on a Hurricane Hunter plane.

The aircraft, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), shuddered and bucked in turbulence that subjected it to a thrashing 3.8 times the force of gravity, threatening the plane’s structure. The plane “over-G’d,” meaning the storm’s impact on the plane exceeded the 3.0-Gs limit of its frame and required inspection before continuing to fly missions. The researchers had to fly out of the storm.

“I've been on some pretty turbulent flights, but this is the first one that over-G'd,” said Wadler, an assistant professor of Meteorology who has flown into hurricanes since 2017. “It takes extreme vertical velocities to get to that point. Things inside the plane went flying and were basically suspended in the air.”

Among hurricanes to make landfall in the Atlantic basin, Melissa is tied with two others as the strongest ever recorded in terms of its maximum wind strength. Its minimum pressure, another indicator of the storm’s strength, was the third lowest ever recorded. By Wednesday, the storm had caused more than 30 deaths and extensive damage on island nations in the Caribbean, including Haiti, Jamaica and Cuba.

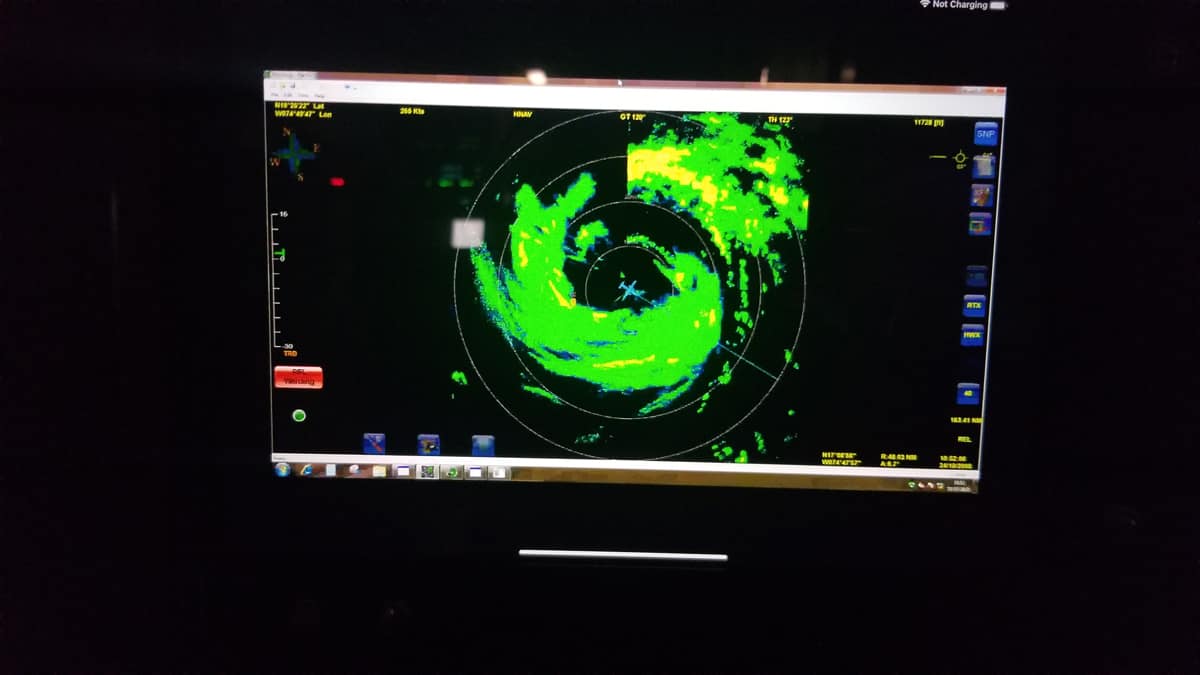

The NOAA Hurricane Hunter plane can be seen inside the eye of Hurricane Melissa in this radar tracking image. (Photo: Josh Wadler/Embry-Riddle)

Wadler’s research aboard the Hurricane Hunter aircraft involves dropping uncrewed aerial systems, or drones, from the plane to help map the structure and development of a storm, important information for forecasters and local officials responsible for making decisions regarding storm preparation.

“We’re there to get National Hurricane Center the data they couldn’t get otherwise,” Wadler said, adding that during the flights he is in contact with the center, which requests certain information while the drone is getting measurements and transmitting them.

Because of the ongoing shutdown of the U.S. government, which suspends government research, Wadler’s flight into the hurricane required an exemption, he said.

Small but mighty describes Melissa and other hurricanes, in that the power of small-radius hurricanes is more concentrated. The aborted flight Wadler flew on was heading through a compact eyewall, which in photos resembled a towering enclosure of thick, roiling clouds.

“It was a pretty small eyewall,” and was crossed relatively quickly, Wadler said. “So the really nasty stuff was probably somewhere from 30 seconds to a minute.”

Wadler said turbulence he experienced on a flight into Hurricane Ian in 2022 was worse because it involved side-to-side and up-and-down motions. He is eager to subject data from the aborted flight into Melissa to a method he devised and published earlier this year to quantify how turbulence is experienced in different areas of the plane.

“I’d like to run my method for this flight,” he said, “and see how it compares.”

Michaela Jarvis

Michaela Jarvis