Stormy Weather

On Jan. 2, 1999, a pilot flying a single-engine, piston-powered aircraft under visual flight rules departed Walgett, on the eastern side of Australia, and headed for Merriwa, on the continent’s westernmost edge.

The aircraft never reached its destination. At 3,600 feet above mean sea level, the plane sailed through a cloud base. Without instruments, the pilot was flying blind. Just above the clouds, the plane collided with trees at the top of a ridge and burst into flames, the Australia Transport Safety Board reports. The passenger survived, but the pilot later died from burn injuries.

This scenario — a pilot licensed to fly based on visual cues who encounters meteorological conditions requiring instrument-based navigation — is all too common, says Yolanda Ortiz, a graduate student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

“Clouds blow in and degrade visibility, and that can happen more quickly than you might think,” Ortiz notes. “General aviation pilots who are not instrument-rated are incredibly vulnerable in that type of situation.”

Making matters worse, Embry-Riddle research shows general aviation (GA) pilots often don’t know how to interpret weather forecasts and observation displays. That’s why Ortiz and fellow graduate student Jayde King spent nine sweltering days collecting data from GA pilots at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s notoriously overwhelming AirVenture fly-in event in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

“Rain or shine, Yolanda and I were literally running all around the show with clipboards, test booklets and information scanners,” King laughs. “We had to get it done.”

Their goal was to give a weather-knowledge exam to as many GA pilots as possible.

The Oshkosh data, combined with additional results collected on Embry-Riddle’s campus in Daytona Beach, Florida, paint a grim picture of weather knowledge among GA pilots.

When tested on their knowledge of 23 types of weather information, from icing forecasts and turbulence reports to radar, 204 GA pilots were stumped by about 42 percent of the questions, says lead researcher Elizabeth Blickensderfer, a professor in the university’s Department of Human Factors and Behavioral Neurobiology.

The findings, published in the April 2018 edition of the International Journal of Aerospace Psychology, are worrisome because GA pilots flying smaller planes at lower altitudes, usually with minimal ground-based support, have higher weather-related accident and fatality rates. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reports that in fiscal year 2017, 347 people died in 209 general aviation accidents. According to the FAA, a failure to recognize worsening weather is a frequent cause or contributing factor of accidents, and most weather-related GA accidents are fatal.

Improved testing of GA pilots is needed, Blickensderfer says, noting that in 2014, the National Transportation Safety Board named “identifying and communicating hazardous weather” a top priority for improving safety. Presently, however, the FAA’s Knowledge Exam allows pilots to pass even if they fail the weather portion of the test.

To conduct their study, the Embry-Riddle researchers carefully reviewed what the FAA expects GA pilots to know about weather. Next — in consultation with Thomas A. Guinn, associate professor of meteorology and co-principal investigator, as well as Robert Thomas, a gold seal certified flight instructor and an assistant professor of aeronautical science at Embry-Riddle — the team developed a 95-question exam aligned with the FAA’s expectations as well as currently available aviation weather technologies.

Four categories of GA pilots scored as follows:

- Instrument-rated commercial pilots achieved the highest scores, with a 65 percent accuracy level.

- Instrument-rated private pilots ranked second, with 62 percent correct responses.

- Private pilots flying without an instrument rating scored 57 percent.

- Students correctly answered only 48 percent of the questions.

Overall, the mean score across all 204 pilots was 57.89 percent.

Inscrutable Weather Displays

Blickensderfer emphasizes, however, that her research should not be interpreted solely as a symptom of faulty pilot training. “I don’t want to blame the pilots for deficiencies in understanding weather information,” she says. “We have to improve how weather information is displayed so that pilots can easily and quickly interpret it. At the same time, of course, we can fine-tune pilot assessments to promote learning and inform training.”

What kinds of questions are asked on the Embry-Riddle exam?

As an example, respondents might be prompted to interpret cryptic METAR (Meteorological Terminal Aviation Routine Weather Report) information, which helps pilots prepare for safe flights: “You notice the comment, ‘CB DSNT N MOV N.’ Based on this information, which of the following is true?” Pilots should understand the METAR comment to mean, “Cumulonimbus clouds are more than 10 statute [land-measured] miles north of the airport and moving away from the airport.”

As another example, pilots might be asked to interpret a ground-based radar cockpit display, which would only show recent thunderstorm activity — not current conditions. Or, the survey might ask pilots to look at an infrared (color) satellite image and determine where the clouds with the highest altitude clouds would most likely be found.

Guinn notes that it’s critical for pilots to assess big-picture weather issues before takeoff. In addition, they need to understand, for instance, that radar displayed inside a cockpit shows what happened up to 15 minutes earlier.

“If you’re flying 120 miles per hour and you don’t understand that there’s a lag time in ground-based radar data reaching your cockpit,” Guinn points out, “that can be deadly.”

Higher-Level Thinking

All test questions were designed to push pilots beyond whatever facts they had memorized, so that “they had to think about it and answer the question using the same thought processes as if they were performing a pre-flight check,” Thomas says.

In other words, these realistic questions are high in “cognitive fidelity,” Blickensderfer notes.

A key component of aviation safety is for pilots to integrate weather information and develop a mental model of weather conditions before they leave the ground. This allows pilots to make better flight decisions if they face deteriorating weather in flight, Ortiz and King say. The questions developed by the Embry-Riddle team will help instructors, display designers and researchers understand how well pilots can do that.

The multi-year research program is funded and sponsored by the FAA’s NextGen Weather-in-the-Cockpit program, with matching support from Embry-Riddle. Blickensderfer, who is president-elect for Division 21 of the American Psychological Association and leader of the education division of the Human Factors and Ergonomic Society, said the work could help guide pilot training and assessments. She also hopes it will inspire more understandable aviation weather products.

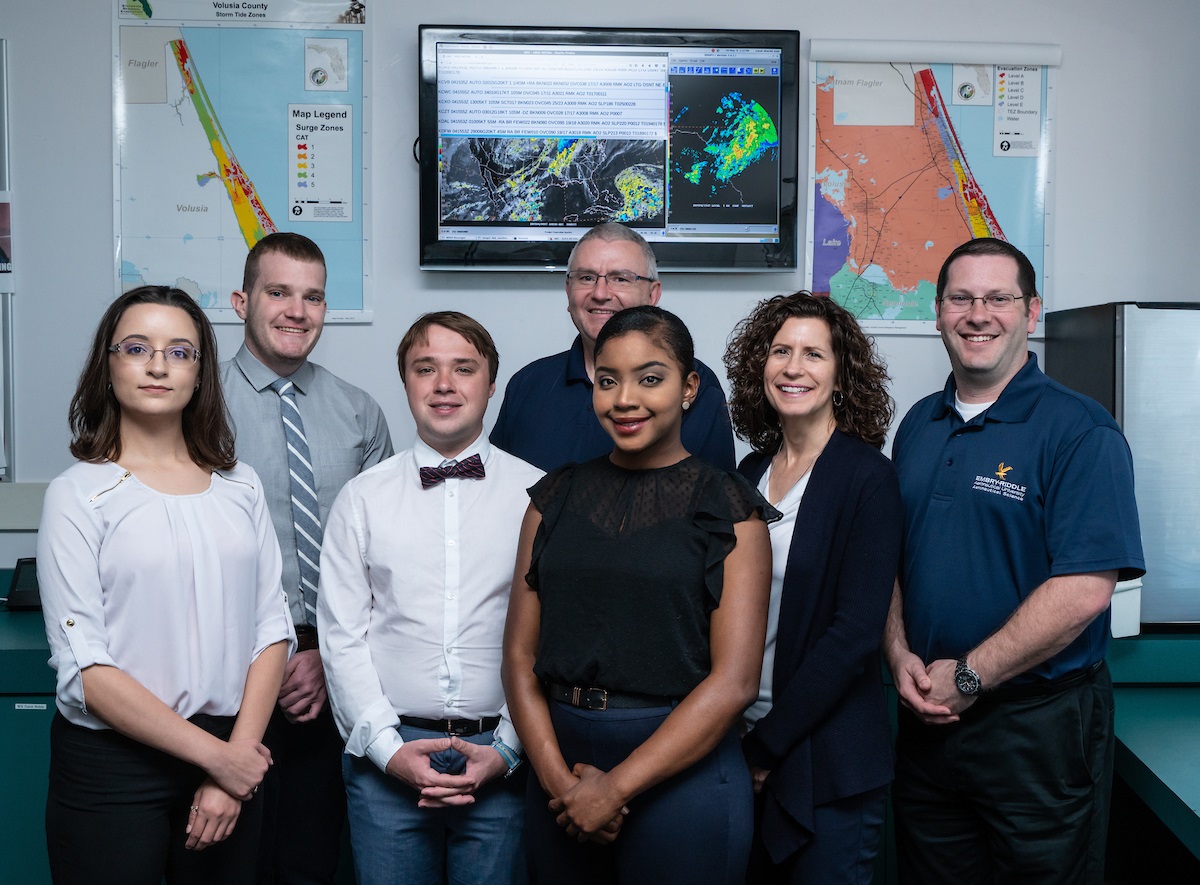

Blickensderfer is continuing to pursue questions about GA pilots and weather knowledge — research conducted in collaboration with Guinn, Thomas, King and Ortiz, as well as former Embry-Riddle faculty member John Lanicci (now at the University of South Alabama) and graduate students Nick Defilippis and Quirijn Berendschot.

A follow-up study, involving about 1,000 GA pilots across the United States, is underway.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the fall 2018 edition of Embry-Riddle’s ResearchER magazine (Vol. 2, No. 2). The ResearchER archives can be found on Scholarly Commons.

Ginger Pinholster

Ginger Pinholster